Jesse Wilkinson (1882-1965)

An Era Begins

Jesse Wilkinson was born September 18, 1882 on a ranch in the small central California coast settlement of La Graciosa, which eventually became what is now the Orcutt area near Santa Maria. The Wilkinson family had migrated from Missouri to California in a covered wagon. They were some of the first settlers in the area.

Most migrants to California were working class people seeking the adventures of a new frontier and a brighter future than what was available to them in the Eastern and Midwestern states. Migration to California was slow and filled with torment through hostile environments, areas with no roads or marked pathways, no developed river crossings, very few towns, and without the civilized conveniences we take for granted today. Early settlements were quite basic and in most cases somewhat primitive because of the limited resources available. These people had only a limited vision of the magnificent and dynamic changes that were in their future.

Jesse was the second of 10 children (5 boys and 5 girls) born to John Wilkinson and Hattie Ann (Stubblefield) Wilkinson. Because of the large number of children in Jesse’s family, the boys left school at an early age and began full-time work. The three oldest boys, Ab, Jesse, and Cleve, joined the cowboy lifestyle; the remaining siblings had other interests.

Miller & Lux

Jesse (often called “Jess” or “Jake”) was a cowboy in every sense of the word. At the age of 12 he left school and went to work for Miller & Lux, the greatest cattle spread ever known. Miller & Lux reportedly owned over one million acres of cattle grazing land in California, Nevada and Oregon plus several ranches leased. Henry Miller was reportedly the only person in the United States to ever own a million head of branded cattle on the range at one time. Bill Stubblefield, Jesse’s uncle, was superintendent for the Miller & Lux southern division, which included Cuyama Valley, Carrizo Plains, and the Buttonwillow area of Kern County.

Jesse rode the rough stock of horses and cowboyed for Miller & Lux for many years. He had the fortune of working with older vaqueros who tutored him in the finer skills of horsemanship and cattle handling. Jesse advanced to one of the company’s top foremen and one of its best riders. He said he broke more wild horses for Henry Miller than he could remember.

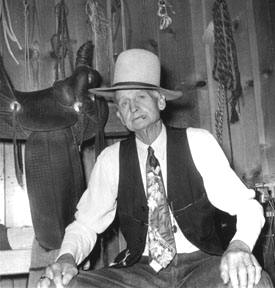

Jesse at the Chimeneas Ranch circa 1934.

Jesse at the Chimeneas Ranch circa 1934.

Horse Breaking

The horses Jesse rode were common bloodline ranch horses that were bred, born, and raised on large open ranges where they learned early in life to handle themselves in several types of terrain and range conditions. These horses were virtually untouched until 5 years old when they were gathered from the range and prepared for use as saddle horses. Horse training lessons were doled out during daily on-the-job training sessions in numerous ranching activities. The cowboy was an unofficial veterinarian who often faced on-the-spot cattle doctoring situations. Roping cattle was standard practice because corrals and cattle handling facilities were often several miles away.

Jesse followed the California vaquero system of horse breaking. All horses were started in a braided rawhide hackamore with horse hair mecate reins. Snaffle bits were almost never used. The horse was ridden for about a year or so in the hackamore while being used for all daily ranching activities. This was an important formative training period for the horse. The horse then advanced to the two-rein system, using a combination of a bosal (a smaller sized hackamore) with horse hair mecate reins while also wearing a bit with bridle reins. This was an important time for gradually advancing from riding in the hackamore to riding “straight up in the bit.” The two-rein transition period usually lasted about a year or so, depending on the progress of the horse. The bit used most often was a spade bit, although a half breed bit was occasionally used. After completing the two-rein training period, the horse was ridden “straight-up in the bit,” which usually continued for the rest of its working career.

Jesse strongly advocated the benefits of allowing a horse to mature before beginning the training process. These horses were to be used as part of several cowboying tasks in a variety of terrains, and he insisted that they needed mental and physical maturity to endure conditions that probably could not be handled by young, immature horses. He reasoned that before 5 years old a horse’s bones, tendons & ligaments, teeth, and mind are not ready for the difficult tasks that may be required. He insisted that starting a horse any younger than 5 years old was inviting problems that may cripple it for life, and therefore render it useless for the necessary ranch work.

California vaquero horses were especially admired for their responsiveness to feather-light handling of the reins and their graceful movements while involved in numerous ranching activities. Jesse and his brother Ab were well-known for having outstanding horses.

Jesse and Ab at the Chimeneas Ranch, circa 1935.

Jesse and Ab at the Chimeneas Ranch, circa 1935.

Ab riding a hackamore horse at the Chimeneas Ranch, circa 1935.

Ab riding a hackamore horse at the Chimeneas Ranch, circa 1935.

Jesse while working at the Camatta Ranch.

Wild Cattle

Cattle went to market on foot in those days, or at least as far as the loading pens at the railroads. Jesse drove cattle many times across areas where Maricopa, Taft, McKittrick, Devil’s Den, and Avenal now stand, before there were any buildings and the only inhabitants in that country were jackrabbits and horned toads. On one drive Jesse and others swam 3,500 head of cattle over the Miller & Lux canal while moving them to market. On another occasion, 60,000 head of cattle under four Miller & Lux outfits were gathered at Buttonwillow to be graded and shipped. On another occasion a team of 60 Miller & Lux vaqueros took four wagons to Deep Wells to brand a few head of cattle Henry Miller had bought; the few head were 15,000 two-year-old steers – they roped and branded them all.

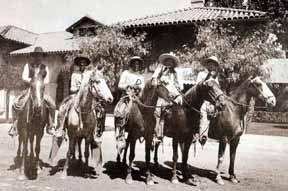

Jesse (second from left) and other vaqueros in front of the Beale Library after a cattle drive that ended near Bakersfield.

Jesse at the Jobe Ranch in the Carrizo Plains

area of San Luis Obispo County.

Jesse and Ab while working at Ozena, CA, near the Cuyama River and Frazier Park.

Jesse and Ab while working at Ozena, CA, near the Cuyama River and Frazier Park.

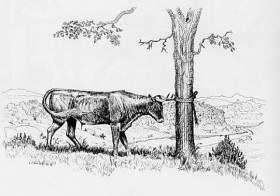

Many completely wild cattle, as wild as deer, roamed the hills in those days. Some of the most exciting moments during Jesse’s boyhood took place in the Ozena and Pine Mountain areas which sheltered many herds of wild cattle. Jesse and his companion riders would rope the wild cattle with their riatas, throw the animal down and tie it’s feet together with a piece of grass rope, and then with another grass rope tie the animal by its horns to a tree. After securing the animal to a tree, the grass rope binding its feet was cut loose and the wild steer was left there overnight, tethered by the horns to the tree. During the night the wild steer would attempt to get away, walking around the tree and frequently pull back on the rope tied around its horns. The constant friction caused the skin around the horns to become quite tender and sensitive. The next morning the riders would return, put a riata around the animal’s horns, and cut the grass rope free. With the riata around the tender and sensitive area of the horns the steer would quietly follow the rider with very little resistance.

A wild steer tethered to a tree.

Wild Elk

Jesse vividly recalled a Tule Elk relocation activity that took place in 1904, when he was 22 years old.

The Tule Elk (native to California’s central valley) were significantly declining in numbers during the late 1800s and early 1900s. Although they were declining in numbers, they were causing significant crop damage in the Buttonwillow area of Kern County. A government preservation program was developed that included relocating some of the elk herd to other areas of the state. Henry Miller had significant land holdings in the Buttonwillow area, he was a strong advocate for Tule Elk protection, and he cooperated with the government’s elk preservation programs.

In 1904 government officials decided to relocate some of the elk herd from the Buttonwillow area to Sequoia National Park in the Sierra Nevada Mountains east of Bakersfield. The elk were to be gathered by highly skilled cowboys and herded into specially designed catch pens. They would then be transported by train to Sequoia National Park. Some of the highly skilled Miller & Lux vaqueros were chosen to assist in the elk gathering because of their experience handling wild cattle. Jesse was one of the men chosen for this task.

Miller & Lux cattle pens and loading chutes were already located nearby at Lokern, so wings were extended out to better facilitate the riders when they began to drive the elk into the catch pens. Jim Ogden, manager of the Buttonwillow Ranch where the elk were located, was in charge of the drive. His orders were that only as a last resort, if the elk were escaping, as many as possible should be lassoed.

Crews of men on horseback, about sixty men, were placed in a series of relays for handling the elk. The first group of riders drove a large band of elk about a mile and a half to a relay crew. As soon as the second crew took over the elk spooked and scattered to the countryside of the Elk Hills area. The scattered elk seemed to be running in every direction. Jesse saw Ogden getting his riata ready to catch an elk, so Jesse built a loop in his riata.

Ahead of Jesse was a big bull elk with large antlers. Bill Stubblefield, Jesse’s uncle, was in the lead and Jesse was right behind him. Bill took after the big bull, swinging his riata. Just as Bill threw his loop the running elk jumped sideways, and the loop fell to the ground. Jesse followed with a toss and caught the feisty bull elk around the antlers, and he dallied his riata around the saddle horn, while the rest of the elk and cowboys raced onward.

There he was on one end of the riata, and a wild elk on the other end. He thought, “Well, I can throw and tie down a wild cow, so maybe I can throw and tie down a wild elk. I’ll try.” He did. With all the spunk of his youth, Jesse threw the animal and tied it down (immobilized it by hog-tying all four feet together with a short piece of rope).

He was quickly back in the saddle and went after a cow elk, which he also caught and tied down.

By this time the elk and other cowboys were out of sight. However, along the rim of the hill he saw two dust clouds, moving fast. Two men were riding hard about a mile behind a spike elk. Jesse rode his horse into a washout and waited unnoticed. When the spike elk was near he jumped his horse out of the washout, lassoed the elk, and tied it down too.

Out of the entire elk herd only ten were captured that day. All were roped, including the three Jesse caught and tied down.

Wagons were used for taking the captured elk to the railroad loading pens. Because elk are extremely nervous, one of them died before it could be loaded into a wagon. The antlers of the big bull elk Jesse caught were so large that the animal had to be dehorned so he could fit through the loading chute and into the railroad car.

The big bull elk was the only one to survive the train ride to Sequoia National Park. The others all died in transit. When the big bull elk was turned loose in the park he was apparently one very furious animal after the entire ruckus. He saw a buck deer nearby and charged for a battle to the death, not realizing he had no antlers. Because the elk’s antlers had been removed, the buck deer made short work of him, killing the bull elk. Upon that occurrence, all of the elk that were captured had died. The elk drive was a total failure.

Photos and descriptions of the 1904 elk relocation effort are included in California Fish & Game and other historical and government publications. An article featuring the elk drive published in a San Francisco newspaper several months after the event included a picture of Jesse on horseback with the large bull elk at the end of his riata.

The following photographs of the 1904 elk drive are available courtesy of the U.C. Berkeley Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, and courtesy of the California Academy of Sciences. Photographs were taken by John Rowley and C. H. Merriam.

Big bull elk tied to fence at the Miller & Lux Buttonwillow corrals.

Sawing antlers off the roped and tied big bull elk.

Loading an elk into a railroad car.

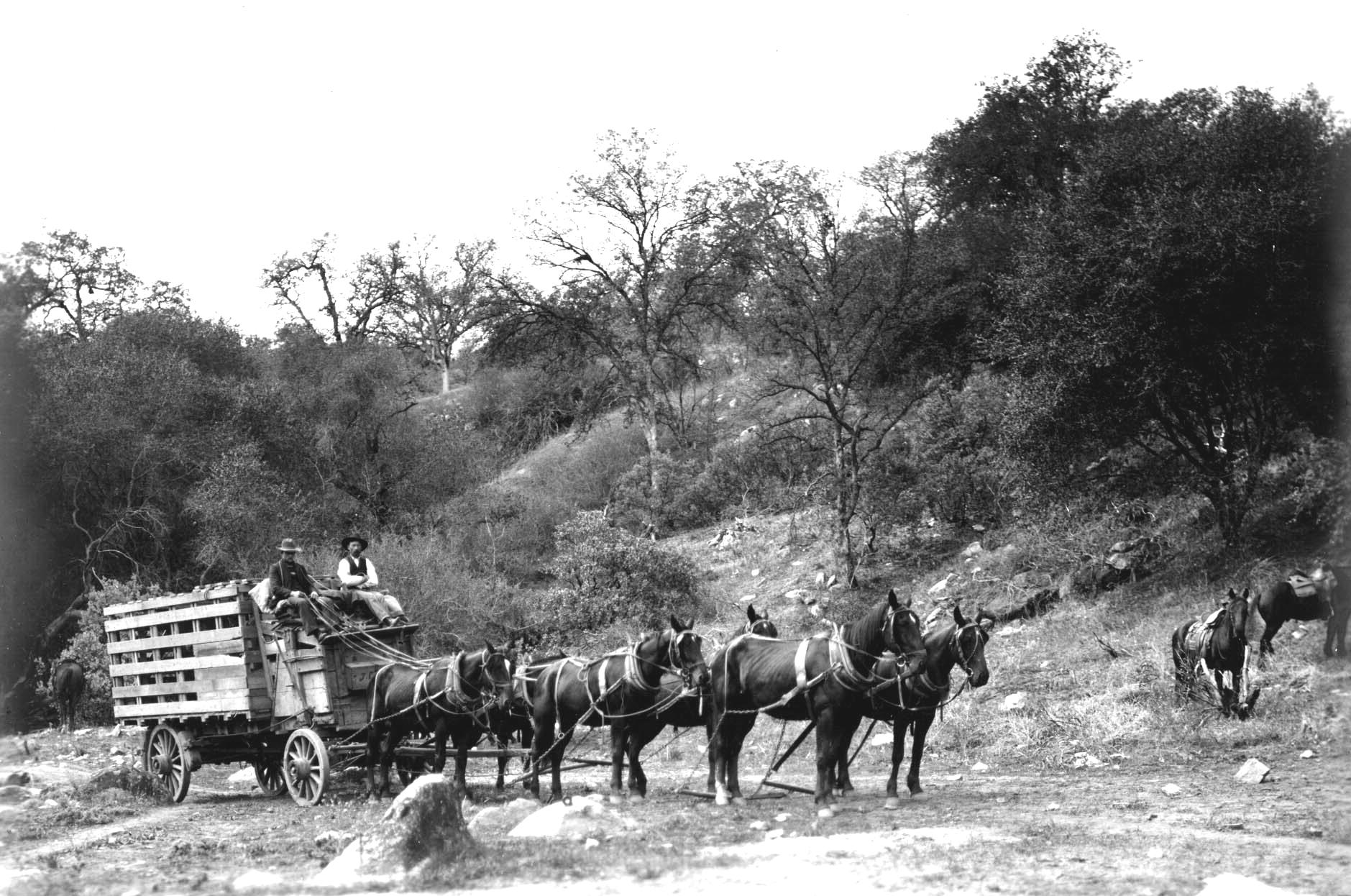

Horse drawn wagon used for hauling elk.

Special Note: Henry Miller was a real hero for the Tule Elk because he made significant efforts to protect them. Although the 1904 elk drive was not successful, Tule Elk have subsequently been relocated from the Buttonwillow area to government supervised elk preserves in other parts of the state. A Tule Elk Preserve near Buttonwillow (established in 1932) is managed by the state parks system.

Family Man

In 1908 Jesse married Nora Ethel Jobe, daughter of Sam Jobe and Eliza (Blackburn) Jobe. Sam Jobe was a Pony Express rider, a stagecoach driver, and a personal friend of Buffalo Bill Cody. Nora was the first non-Indian child born in the Carrizo Plains area of San Luis Obispo County. Jesse and Nora had four children (2 boys and 2 girls).

Jesse and Nora Wilkinson at their 50th wedding anniversary celebration in 1958.

Bit maker Abby Hunt and his wife Alma at the Wilkinson’s home for

Jesse and Nora’s 50th wedding anniversary celebration.

Rawhide Braiding

Jesse learned the art of rawhide braiding as a boy. He watched with fascination as the older cow-hands made the riatas, hackamores, bosals, reins, hobbles, quirts, etc. that they needed. He asked one of these skilled craftsmen if he would teach him. Jesse was told to ask his uncle for a “green” cow hide and he would show him how to do it. His teacher had to be away for a while, so Jesse worked on some rawhide gear by himself. Upon the teacher’s return Jesse quite proudly showed him the work he had done. But he was shown where some of the strands were not smooth enough, and he was told to take it apart and do it over. His teacher insisted on perfection, a trait that Jesse adopted and followed throughout his life.

Jesse was a serious student who worked hard at perfecting rawhide working techniques. Because he had the fortunate opportunity to also use all of the rawhide items he made, he perfected all aspects of the work to make them ideally functional for the user.

Ab and Jesse preferred 85 foot riatas for open range work, and when a riata got down to 65 feet through wear and breakage, they made a new one.

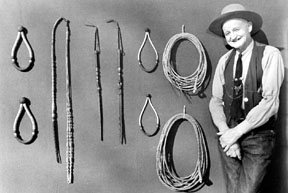

Jesse circa 1930 with several rawhide riatas and other horse gear he made.

Jesse’s rawhide work was widely known. He sold it to patrons from Canada to South America, as well as many areas of the United States. Among his customers were such notables as philosopher and humorist Will Rogers, western artist Ed Borein, western movie actor Buck Jones, author and historian Seldon Spaulding, as well as numerous ranchers, buckaroos and collectors. His rawhide work can be found in museums and private collections in many parts of the world.

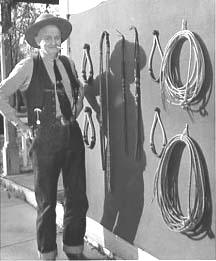

Jesse at age 72 with samples of his rawhide work.

A picture of Jesse with samples of his rawhide work is included in books by Bruce Grant entitled “How to Make Cowboy Horse Gear” and “Encyclopedia of Rawhide and Leather Braiding.” Bruce told Jesse that these books never would not have been completed without his help.

Jesse’s grandson, Ernest Morris, asked Jesse to teach him the skills and “secrets” of rawhide braiding. Jesse was aware that his own reputation would forever be associated with Ernie’s work. He told Ernie that he would teach him the rawhide business from A to Z if he would make two promises. The two promises were: “never cheat the people,” and “do what he told him to do, the way he told him to do it.” Ernie agreed. Jesse then said, “If you can’t get it, I want you barking at the hole.” “Barking at the hole” essentially meant to pay attention and be diligent in efforts to understand and learn, try on your own as much as possible, and then to ask for help if needed. Ernie was a diligent student. The two spent numerous hours together working rawhide and discussing cowboying activities of the past.

Jesse tutoring Ernie on some finer points of rawhide work.

Ernie with a number of hackamores he made.

Other Perspectives

Jesse lived during a period of the great Spanish and Mexican ranchos of California, working daily during his youth with many older vaqueros. Ranching areas were massive open ranges with a variety of terrains. Fences dividing the ranchos into smaller areas were almost non-existent. The cattle that ranged on ranchos took on the characteristics of wild beasts, many seeing men or horsemen on only limited occasions. Jesse cowboyed on ranches in Kern, Kings, Monterey, San Luis Obispo, Santa Barbara, and Ventura counties of California.

He was primarily a self-taught man, reading numerous books and publications for both learning and enjoyment purposes. He was physically hardened by daily tasks, he took pride in his appearance, and he cast a handsome cowboy figure.

Jesse at age 26.

Jesse at age 70.

Hard work and the environment of nature kept him riveted to the truth. He was a no nonsense man who lived his life with impeccable honesty and unwavering determination. His shoulder never left the wheel when there was work to be done. He retired from cowboying at the age of 70, and continued working rawhide until the age of 81.

When asked why he never drank alcoholic beverages, he said he saw it make people act like fools, and he saw it ruin the lives of many good people and their families. He wanted nothing to do with anything that could cause those results.

In 1958 Jesse was honored as Marshall of the annual Pioneer Day parade in Paso Robles. His brother Ab served as deputy Marshall for the event.

Jesse and Ab at the 1958 Pioneer Day Parade (Paso Robles, CA).

This is the way they and their horses were equipped while working everyday. This was the last time either of them rode horseback.

Because of their active lifestyles, the Wilkinson family was seldom all together at one time. The first time all five Wilkinson brothers sat down together for a meal at the same time was in 1960 when Jesse was 77 years old.

The five Wilkinson brothers in 1960 at their first ever meal together at the same time.

From left to right (youngest to oldest) – John, Ira, Cleve, Jesse, Ab.

The cowboying lifestyle Jesse lived had many risks and dangerous incidents, many hardships, and it did not pay well. Those who did it either loved their work, or they moved on to another occupation. Jesse loved his work.

Jesse lived a full and colorful life that contemporary cowboys can only dream about. Amazingly, he never broke any bones.

Jesse at 80 years old.

During Jesse’s lifetime there were 15 different US presidents, 16 different California governors, and two world wars. Technology and personal conveniences advanced beyond wildest imaginations. He witnessed industrial, social, environmental, and economic revolutions that changed the lives of all of us that followed, including the life of the cowboy.

An Era Ends

Jesse had all of his wit, spirit and faculties all the way to the end. On June 21, 1965 Jesse passed on to join the other vaqueros who had gone before him. I’m sure a good horse was saddled and waiting for him when he arrived. His wife, Nora, and his grandson, Ernest Morris, were at his bedside.

A riata made by Ernie Morris is proudly displayed on Jesse’s everyday working saddle.

This saddle was made by Visalia Stock Saddle Co. circa 1934.

The decorated and personalized cantle of Jesse’s everyday working saddle.